What I’m Reading

To keep track of what I’m reading, I’ll update this list as I go along. I’ll be sharing more elaborate thoughts on the books on this blog (sometimes), and sharing a few in Marginalia, a monthly (ish) newsletter.

2024:

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

2023:

The Color of Water by James McBride

It’s a Shame About Ray by Jonathan Seidler

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin

East West Street by Phillippe Sands

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan

Jews Don’t Count by David Baddiel

In the Garden of Beasts by Erik Larson

Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout

2022:

Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout

Anything is Possible by Elizabeth Strout

The Candy House by Jennifer Egan

Transit by Anna Seghers

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado

The Arsonist by Chloe Hooper

The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer

Four Thousand Weeks by Oliver Burkeman

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward

Lost & Found by Kathryn Schultz

Empire of Pain by Patrick Radden Keefe

The Hours by Michael Cunningham

2021:

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

The Book of Delights by Ross Gay

Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout

Still Life by Sarah Winman

Writers & Lovers by Lily King

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

Austerlitz by W.G. Sebald

The Yellow House by Sarah M. Broom

Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat by Samin Nosrat

Zaitoun by Yasmin Khan

Midnight Chicken by Ella Rishbridger

Nobody Will Tell You This But Me by Bess Kalb

Know My Name by Chanel Miller

The Living Sea of Waking Dreams by Richard Flannagan

More Than A Woman by Caitlin Moran

Homeland Elegies by Ayad Akhtar

Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell

Upstream by Mary Oliver

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

Shakespeare by Bill Bryson

2020:

Intimations by Zadie Smith

Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell

Vesper Flights by Helen McDonald

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart

Sula by Toni Morrison

Mayflies by Andrew O’Hagan

Having and Being Had by Eula Biss

Just Like You by Nick Hornby

White Teeth by Zadie Smith

High Fidelity by Nick Horby

Caste by Isabel Wilkerson

Apeirogon by Colum McCann

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

Everything I Know About Love by Dolly Alderton

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin

Figuring by Maria Popova

The Education of an Idealist by Samantha Power

Weather by Jenny Offill

Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo

So Long, See You Tomorrow by William Maxwell

Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell

The Topeka School by Ben Lerner

No Friend But the Mountains by Behrouz Boochani

2019:

Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

Beloved by Toni Morrison

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill

Strangers Drowning by Larissa Macfarquhar

Stop Being Reasonable by Eleanor Gordon-Smith

Congratulations, by the way by George Saunders

Winter by Ali Smith

Autumn by Ali Smith

Washington Black by Esi Edugyan

Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels

The Friend by Sigrid Nunez

Lanny by Max Porter

Talking to My Daughter About the Economy: A Brief History of Capitalism by Yanis Varoufakis

Stop Being Reasonable by Eleanor Gordon-Smith

The Story of My Teeth by Valeria Luiselli

Lake Success by Gary Shteyngart

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing

In The Distance by Hernan Diaz

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitzky and Daniel Ziblatt

The Tyranny of Choice by Renata Salecl

Night by Eli Wiesel

Happy Ever After by Paul Dolan

Fox 8 by George Saunders

The Library Book by Susan Orlean

Milkman by Anna Burns

2018:

Small Fry by Lisa Brennan-Jobs

An American Marriage by Tayari Jones

Silence by Erling Kagge

Becoming by Michelle Obama

The Principles of Uncertainty by Maira Kalman

The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy

Things I Don’t Want To Know by Deborah Levy

The Accusation by Bandi

New Jerusalem by Paul Ham

Shell by Kristina Olsson

Normal People by Sally Rooney

Londoners: the days and nights of London now—as told by those who love it, hate it, live it, left it and long for it by Craig Taylor

300 Arguments by Sarah Manguso

Ongoingness: The End of a Diary by Sarah Manguso

Man Out of Time by Stephanie Bishop

The Children’s House by Alice Nelson

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan

A Honeybee Heart Has Five Openings by Helen Jukes

Less by Andrew Sean Greer

The History of Love by Nicole Krauss

Sabrina by Nick Drnaso

Hot Milk by Deborah Levy

Heartburn by Nora Ephron

Ms. Ice Sandwich by Meiko Kawakami

The Complete Persepolis by Marjane Rastrapi

Asymmetry by Lisa Halliday

Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo

The 78-Storey Treehouse by Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton (with my son)

Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay In 40 Questions by Valeria Luiselli

The Line Becomes A River by Francisco Cantú

The Other Side of the World by Stephanie Bishop

Evacuation by Raphael Jerusalmy

Tin Man by Sarah Winman

The Home-Maker by Dorothy Canfield Fisher

The Mothers by Brit Bennett

Lullaby by Leila Slimani

Look At Me by Mareike Krugel (reading copy, out in March)

Lost Connections by Johann Hari (reading copy, out in February)

The 65-Storey Treehouse by Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton (with my son)

Peach by Emma Glass (reading copy, out in February)

Hourglass: Time, Memory, Marriage by Dani Shapiro

The Spare Room by Helen Garner

The Giraffe and the Pelly and Me by Roal Dahl (with my son)

Esio Trot by Roald Dahl (with my son)

The 52-Storey Treehouse by Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton (with my son)

The 39-Storey Treehouse by Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton (with my son)

2017:

I Remember Nothing by Nora Ephron

The 26-Storey Treehouse by Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton (with my son)

The Unknown Unknown: Bookshops and the Delight of Not Getting What You Wanted by Mark Forsyth

The 13-Storey Treehouse by Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton (with my son)

The Ice Palace by Tarjei Vesaas

Kneller’s Happy Campers by Etgar Keret

Hope: A Tragedy by Shalom Auslander

James and the Giant Peach by Roald Dahl (with my son)

Turtles All The Way Down by John Green

Where’d You Go, Bernadette by Maria Semple

The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip by George Saunders

Today Will Be Different by Maria Semple

The Book of Emma Reyes by Emma Reyes

Suddenly, A Knock On The Door by Etgar Keret

The Seven Good Years by Etgar Keret

When Things Fall Apart by Pema Chodron

Devotion by Dani Shapiro

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders

Swing Time by Zadie Smith

Transit by Rachel Cusk

The Gifts of Reading by Robert Mcfarlane

Outline by Rachel Cusk

Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

The Outrun by Amy Liptrot

My Name is Lucy Barton by Elizabeth Strout

Dear Ijeawele, or a Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Goodbye, Vitamin by Rachel Khong (reading copy, out in June 2017)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy

The Fault in Our Stars by John Green

Night Swimming by Steph Bowe (reading copy, out in April 2017)

The Course of Love by Alain de Botton

The Vegetarian by Han Kang

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

The Emigrants by W.G. Sebald

Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance

Things Might Go Terribly, Horribly Wrong by Kelly Wilson

2016:

On Reading, Writing and Living with Books

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

Darkness Visible by William Styron

Dying: A Memoir by Cory Taylor

The Sellout by Paul Beatty

The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Epic of Gilgamesh translated by Andrew George

Dubliners by James Joyce

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

The Examined Life by Stephen Grosz

Grief Is the Thing with Feathers by Max Porter

Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes by Janet Malcom

The Art of Reading by Damon Young

Gratitude by Oliver Sacks

Cathedral by Raymond Carver

A Sheltered Woman by Yiyun Li

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

The Bricks That Built The Houses by Kate Tempest

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald

Eating Animals by Jonathan Safran Foer

Slaughterhouse 5 by Kurt Vonnegut

Franny and Zooey by J.D. Salinger

The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes

Stoner by John Edward Williams

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

The Opposite of Loneliness by Marina Keegan

Levels of Life by Julian Barnes

The Tall Man by Chloe Hooper

Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit

A Field Guide to Getting Lost by Rebecca Solnit

Matilda by Roald Dahl

A Grief Observed by C.S. Lewis

How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life by Russ Roberts

How Proust Can Change Your Life by Alain de Botton

All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews

M Train by Patti Smith

2015:

Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl by Carrie Brownstein:

A beautiful memoir from the guitarist of the epic and pioneering band, Sleater-Kinney. A true deviation from the regular rock ‘n roll story of destruction, this book is a tale of losing, and then finding yourself, in music.

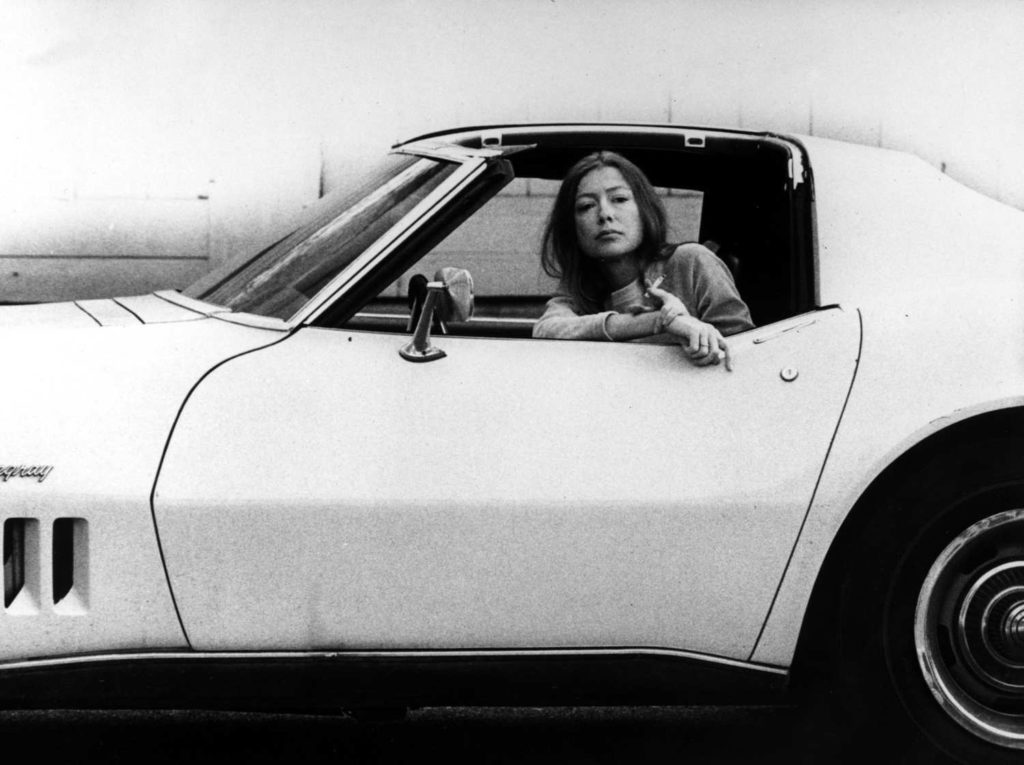

The White Album by Joan Didion

Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke:

A phenomenal, illuminating read, even if you’re not into poetry. In this collection of ten letters, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke advises a nineteen year old fan on love, truth and how to experience the world around you. Some of my favourite bits:

On loving books:

“A world will come over you, the happiness, the abundance, the incomprehensible immensity of a world. Live a while in these books, learn from them what seems to you worth learning, but above all love them. This love will be repaid you a thousand and a thousand times, and however your life may turn, — it will, I am certain of it, run through the fabric of your growth as one of the most important threads among all the threads of your experiences, disappointments and joys.”

On the benefits of living with mystery:

“…have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don’t search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.”

Breakfast of Champions by Kurt Vonnegut

Hiroshima by John Hersey

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Love’s Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy by Irvin D. Yalom

No One Belongs Here More Than You by Miranda July

How to Be Alone by Sara Maitland:

An interesting and illuminating cultural look at loneliness. Part of the School of Life’s stunning “toolkit for life” series, British author Sara Maitland writes on the benefits of going solo. This book is an important take down of one of society’s most unhelpful stories: that people who choose to be alone are doomed to a life full of misery. Through this book I also discovered other writers I fell in love with, particularly Alice Koller, who penned this gem: “Being solitary is being alone well: being luxuriously immersed in doing things of your own choice, aware of the fullness of your own presence rather than the absence of others.”

Hyperbole and a Half by Allie Brosh:

Tore through this in a few hours. So, so good. A few essays are absolutely laugh out loud hilarious (particularly one involving a wild and demented goose), and others are profound in that way only Allie Brosh can be (her pieces on depression represent one of the most human views on the topic I’ve ever encountered). Honestly, this book is perfect.

When I Am Playing with My Cat, How Do I Know She is Not Playing with Me? Montaigne and Being in Touch With Life by Saul Frampton

Slouching Towards Bethlehem by Joan Didion:

A stunningly written collection of meditations on a rich and wide array of topics, from John Wayne, to growing up in California, Joan Baez, Hollywood and the hippies of Haight-Ashbury. I enjoyed every essay more than I thought I would, due probably to Didion’s uncanny ability to make any topic interesting. Two particular pieces though stood out for me, and have been struggling to get them out of my mind since I finished the book: On Keeping A Notebook (a beautiful reflection on the benefits of writing things down) and On Self-Respect (a brave, illuminating essay on the importance of knowing who you are).

Strange Pilgrims by Gabriel Garcia Marquez:

Already having been a huge fan of Marquez, I was ecstatic when I found a used copy of a slim yet sublime collection of his short stories. While rummaging through tomes at a local used book stall, I stumbled upon this little volume I knew nothing of, began to read and was naturally hooked from the very first sentence. Titled Strange Pilgrims because of the long, wayward method in which the stories came to life, in this collection you’ll find fables of love, death, loneliness and the nagging power of the past.

How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in one question and twenty attempts at an answer by Sarah Bakewell:

The question of “how to live” completely obsessed Renaissance writers, but no one tackled it with such brilliance as Michel de Montaigne, a government worker, nobleman, and winegrower who lived in southwestern France from 1533 to 1592. He is considered the creator of the essay – the art of self-reflection on paper. And in the twenty years that he wrote his famous “essays” (107 of them), Montaigne covered everything from the existential to the mundane: how to endure the loss of a loved one, the benefits of thumbs, how to get along with people, how to deal with violence, how to dress. In this biography, writer and philosophy scholar Sarah Bakewell chronicles Montaigne’s life through the answering of one question: how do you live? A truly enlightening, mind-expanding read on not just the man’s life, but on death and the art of living.

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius:

I’ve picked it up countless of times since I first read it over a year ago — it is by far the best book of practical philosophy I have ever encountered. Written by Marcus Aurelius, Roman Emperor from 161 to 180 AD,“Meditations” is a collection his private thoughts and ideas on how to be present, humble, and self-disciplined. Shelved in “books for life.”

Staring at the Sun by Irvin D. Yalom:

An encouraging and compassionate approach to our mortality. While it’s marketed as a primer on how to deal with death anxiety, to me this work is much more about how to live rather than how to die. It completely shifted my perspective on the choices we get to make every day: what we value, the stories we tell, how we spend our time. One question Yalom asks has never left my mind: If you were asked whether you would live your life all over again, would you? While the physicality of death destroys us, the idea of death imbues us with life.

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion:

Written in the only way Didion really knows how: hauntingly. This is a difficult book to get through, not because of the way in which it is written (it is a joy to travel through her sentences), but rather because of its topic. Written after her husband’s sudden death, The Year of Magical Thinking is Didion’s memoir recounting how she handled the loss of her partner. It is an exceptional meditation on grief (a topic, Didion notes, strangely absent in literature), love and the vicissitudes of fortune. One reviewer said he couldn’t imagine dying without this book. That is exactly how I feel.

The Art of Stillness by Pico Iyer:

Finished this delightful, slim yet meaningful book in one sitting. Pico Iyer, the celebrated travel writer, extolls on the benefits of stillness, presence and finding the time to reflect on our human experience. I have yet to find a better description of stillness and its role in creating a rich and meaningful life: “To me, the point of sitting still is that it helps you to see through the very idea of pushing forward; indeed, it strips you of yourself, as of a coat of armour, by leading you into a place where you’re defined by something larger. If it does have benefits, they lie within some invisible account with a high interest rate, but very long-term yields, to be drawn upon at that moment, surely inevitable, when a doctor walks into your room, shaking his head, or another car veers in front of yours, and all you have to draw upon is what you’ve collected in your deeper moments.”

I Feel Bad About My Neck: And Other Thoughts On Being A Woman by Nora Ephron:

Impossible not love Nora Ephron. As funny as she is profound, this book of essays (on hating your neck, living in New York, parenting, illness, reading and more) is the kind of book you never want to finish. This thought, on reading, struck a chord: “Reading is everything. Reading makes me feel I’ve accomplished something, learned something, become a better person. Reading makes me smarter. Reading gives me something to talk about later on. Reading is the unbelievably healthy way my attention deficit disorder medicates itself. Reading is escape, and the opposite of escape; it’s a way to make contact with reality after a day of making things up, and it’s a way of making contact with someone else’s imagination after a day that’s all too real. Reading is grist. Reading is bliss.”

The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh by Vincent Van Gogh:

This book is tremendous. A weighty tome (nearly 800 pages), it’s the truest inside look into the heart and mind of an artist. In his letters to his younger brother Theo (who supported Vincent throughout his entire life as a painter), Van Gogh reveals his views on love, art, creativity and what it means to be not only a good artist, but a good human being. What I found most astounding was just how hard Van Gogh worked to develop his talent as an artist. While he did seem to have a natural ability to observe the world that lay before him (his descriptions of scenery are as almost vivid as his paintings), Van Gogh spent years learning the techniques of both drawing and painting, becoming better as time passed. It wasn’t until he moved to the South of France, quite late in his short but prolific career (and where he was influenced by the already growing Impressionist movement), when he began to produce the paintings we know him for today.

Where I Lived, And What I Lived For by Henry David Thoreau:

A lovely, short excerpt from Thoreau’s longer work on his time living near Walden Pond. This small Penguin Great Ideas book includes only a few chapters, though it is bustling with timeless insight, strengthening my desire to read the whole work. There’s a treasure trove of quotable lines on many aspects of modern life: the ills of fashion trends, owning a large home, reading the news, technology. My favourite line, which can, in my opinion, be applied to some aspects of technology today: “Our inventions are wont to be pretty toys, which distracts our attention from serious things. They are but improved means to an unimproved end…”

Born Standing Up by Steve Martin:

A brilliant, touching and unforgettable memoir by one of the world’s most loved comedians. This book is so tremendous. Martin chronicles his early life and his rise to stardom with honesty and sharp wit, making the book an absolute joy to read. Heartbreaking and funny, this book is an inside look into not only the life of a comedian, but also a primer on life as a creative.

Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill:

A phenomenal novel about art, motherhood, marriage and loss. You will feel like you’ll never encounter anything like it again.

On the Shortness of Life by Seneca:

The simplest, most life-altering message I have ever come across: life is long if you know how to use it. In the Roman philosopher’s 2,000 year old mind stretching meditation on time you’ll find a profound and essential message:

“It is not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste a lot of it. Life is long enough, and a sufficiently generous amount has been given to us for the highest achievements if it were all well invested. But when it is wasted in heedless luxury and spent on no good activity, we are forced at last by death’s final constraint to realise that it has passed away before we knew it was passing. So it is: we are not given a short life but we make it short, and we are not ill-supplied but wasteful of it.”

Want to keep up with what I’m reading? Sign up to my newsletter, Marginalia.